The Flat Coated Retriever Rescue Network: News in November 2022

General News

The Flat Coated Retriever Rescue Network (FCRRN) have been active during the autumn responding to a number of contacts that are described in this newsletter. We are happy to respond in line with our key aim and principles(1,2).

On the Internet the prices sought for pure bred flat coated retriever puppies have ranged from £1000 to £1700 and cross bred puppies are being advertised from £400 to £1200. Older flat coated retrievers have been advertised too e.g. aged six months £1000, aged 12 months £1300.

The animal rescue centres remain busy particularly with arrivals of dogs but few flat coated retrievers.

Sadly and despite the efforts of many people, Bodie has not been found. Bodie is a flat coated retriever aged three years who went missing on a walk with his guardian in early July in East Sussex(3). At least the FCRRN’s supporters have not reported other flat coated retrievers going missing this autumn.

Will and Testamentary Disposition; Lasting Power of Attorney

The FCRRN have been contacted by some supporters about the assistance that could be offered in the event of the death of a guardian or a loss of mental capacity. The FCRRN have advised that we are available to try and find a home for a flat coated retriever(s) under these circumstances.

We know of other organisations who offer similar assistance in these circumstances, for example, the Cinnamon Trust; www.cinnamon.org.uk

We are aware that some supporters have changed their Will and Testamentary Disposition or their Lasting Power of Attorney in response to the COVID-19 pandemic and reflections of their own health and mortality. Naturally if someone is considering altering their Will and Testamentary Disposition or their Lasting Power of Attorney then we would recommend you to take legal advice. It would also be prudent to contact the FCRRN so that the relevant information about your flat coated retriever(s) is available if it should be needed.

An example of the wording used by one supporter in their Will and Testamentary Disposition is as follows –

“If any of my dogs shall survive me then I DIRECT that my Executors contact, without delay, the Flat Coated Retriever Rescue Network and arrange for any dogs in my possession at the time of my death to be taken into their care.”

Another supporter has notified the attorney who is identified in their Lasting Power of Attorney that the FCRRN should be contacted for assistance if a lack of mental capacity means that their dogs have unmet welfare and health needs and a new home needs to be found.

Nugget

Nugget (pseudonym) is a female flat coated retriever aged 12 months; her guardians contacted the FCRRN because due to their health problems they have reluctantly decided to rehome Nugget. She seems to be a well-adjusted, lively young girl in good health who her guardians feel needs “something more.”

After extensive discussions with the FCRRN the guardians have decided to manage the rehoming process themselves. The FCRRN have advised the guardians that we remain available to help with finding a suitable home from our list of 25 potential adopters, carrying out the home check, organising the surrender and adoption contracts and the associated paper work, and maintaining contact with the adopting guardians to ensure a high quality of life for Nugget.

Canine polyarthritis or polyarthropathy

1) Background: The FCRRN have received several inquiries coincident inquiries about canine polyarthritis or polyarthropathy particularly regarding the causes and possible associations with inheritance (genetic variations), pregnancy, recent vaccination, or stress. Hence the following commentary –

2) Pre-amble: Canine polyarthritis, synonymous with polyarthropathy, describes a dog showing an abnormal gait and/or lameness and swelling in several joints, for example, the elbows, carpi, stifles (knees), hocks (the three compound joints of the ankle and foot), tarsi. However the signs can be much vaguer including fever, loss of appetite, lethargy, inter alia (Ravicini et alia, 2022).

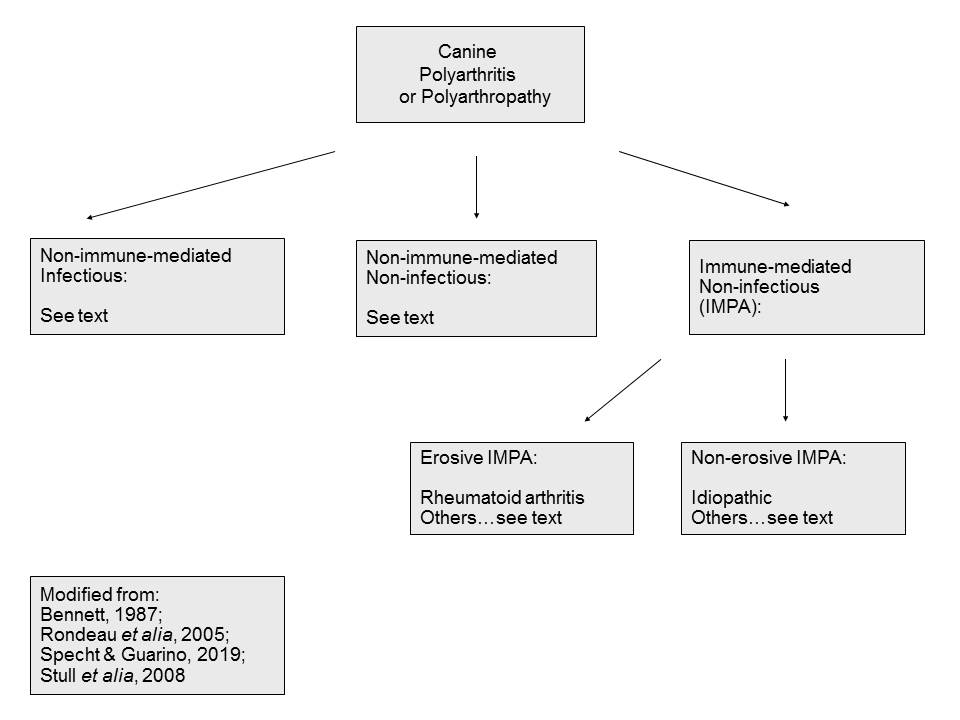

3) Diagnosis: Typically the first step in making the diagnosis is to distinguish between non-immune-mediated polyarthritis and immune-mediated polyarthritis (see Figure One).

The causes of non-immune-mediated polyarthritis include infections, degeneration, trauma, haemorrhage, cancers, and metabolic disorders; these potential causes would all be investigated by the veterinarian (Specht & Guarino, 2019).

4) Classification: There are several classifications of non-infectious immune-mediated polyarthritis (IMPA) (Bennett, 1987; Rondeau et alia, 2005; Stull et alia, 2008). A key distinction is made between erosive and non-erosive IMPA. Erosive IMPA is confirmed on the basis of x-ray tests that show apparent bone lysis within a joint (Shaughnessy et alia, 2016).

Erosive IMPA can be caused by rheumatoid arthritis, breed-associated (e.g. erosive polyarthritis of greyhounds), or erosive polyarthritis of unknown cause (Specht & Guarino, 2019; Wilson-Wamboldt, 2011). Erosive IMPA is rare in comparison to non-erosive IMPA (Shaughnessy et alia, 2016).

Non-erosive IMPA is a complex disease with many possible causes and the most common diagnosis is defined as “idiopathic” which indicates the cause(s) are hidden; 52% to 65% of all cases of non-erosive IMPA are labelled as idiopathic following the exclusion of other causes (Ravicini et alia, 2022; Rondeau et alia, 2005; Stull et alia, 2008).

Other, less common associations between pathological conditions and non-erosive IMPA have been identified –

reactive to an inflammatory or infectious disease elsewhere in the dog;

associated with gastrointestinal or liver disease;

associated with cancer;

associated with drugs e.g. Dobermanns and sulphonamides;

associated with auto-immune disease e.g. systemic lupus erythematosus;

associated with specific breeds e.g. spaniels and polymyositis/polyarthritis syndrome; Bernese mountain dogs, boxers, German short haired pointers, Weimaraners and meningitis/polyarthritis syndrome; beagles and polyarteritis nodosa; Akitas and juvenile polyarthritis; shar peis and amyloidosis. (Stull et alia, 2008).

5) Idiopathic non-erosive IMPA: Many of the pathological conditions associated with non-erosive IMPA have genetic predispositions and some genetic variants have been identified (Friedenberg, 2016; Ollier et alia, 2001). However most cases of non-erosive IMPA have a diagnosis of “idiopathic” and there is insufficient evidence to determine how the identified genetic variants could alter the canine immune system to cause idiopathic non-erosive IMPA (Friedenberg, 2016; Ravicini et alia, 2022).

There is also insufficient evidence to indicate that pregnancy, recent vaccination, or stress are causes of idiopathic non-erosive IMPA; 67 cases (Bennett, 1987), 39 cases (Idowu & Heading, 2017), 73 cases (Ravicini et alia, 2022), 34 cases (Rondeau et alia, 2005), 83 cases (Stull et alia, 2008).

Extensive searching of the literature has not identified that flat coated retrievers are more prone to idiopathic non-erosive IMPA than other breeds.

6) Completing the diagnosis of idiopathic non-erosive IMPA: The diagnosis relies on clinical signs, investigations particularly synovial fluid analysis, and the responses to immunosuppressive therapies. The responses may become the final diagnostic criterion used i.e. if there are clinical improvements through taking the medications and other potential causes have been excluded then the diagnosis of idiopathic non-erosive IMPA can be confirmed (Ravicini et alia, 2022; Stull et alia, 2008).

Arthrocentesis is the name given to the removal of synovial fluid from a joint and in idiopathic non-erosive IMPA the analysis aims to identify significantly raised white blood cell counts, predominantly of neutrophils (Foster et alia, 2014; Specht & Guarino, 2019) and the deposition of circulating immune complexes in the synovium (Ravicini et alia, 2022) hence the term “immune-mediated.” Blood tests are less invasive than arthrocentesis and there are encouraging results that specific blood proteins could be surrogate markers in idiopathic non-erosive IMPA (Foster et alia, 2014).

7) Treatments for idiopathic non-erosive IMPA: Standard treatment protocols have not been created (Ravicini et alia, 2022; Specht & Guarino, 2019). However veterinarians would be expected to discuss the use of analgesics, steroids, non-steroidal anti-inflammatories, and immunosuppressive medications with the guardians. It is beyond the scope of this commentary to review the treatments in more detail or to comment on the prognosis.

8) References:

Bennett, D. (1987). Immune-based non-erosive inflammatory joint disease of the dog. 3. Canine idiopathic polyarthritis. Journal of Small Animal Practice, 28, 909-928.

Foster, J. D., et alia. (2014). Serum biomarkers of clinical and cytologic response in dogs with idiopathic immune-mediated polyarthropathy. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine, 28(3), 905-11. doi: 10.1111/jvim.12351

Friedenberg, S. G., et alia. (2016). Evaluation of a DLA-79 allele associated with multiple immune-mediated diseases in dogs. Immunogenetics, 68(3), 205-17. doi: 10.1007/s00251-015-0894-6

Idowu, O. A., & Heading, K. L. (2018). Type 1 immune-mediated polyarthritis in dogs and lack of a temporal relationship to vaccination. Journal of Small Animal Practice, 59(3), 183-187. doi: 10.1111/jsap.12774

Ollier, W.E., et alia. (2001). Dog MHC alleles containing the human RA shared epitope confer susceptibility to canine rheumatoid arthritis. Immunogenetics, 53, 669-673. doi: 10.1007/s002510100372

Ravicini, S., et alia. (2022). Description and outcome of dogs with primary immune-mediated polyarthritis: 73 cases (2012-2017). Journal of Small Animal Practice, 63(11), 1-7. doi/10.1111/jsap.13565

Rondeau, M. P., et alia. (2005). Suppurative, nonseptic polyarthropathy in dogs. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine. 19(5), 654-62. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-1676.2005.tb02743.x

Shaughnessy, M. L., et alia. (2016). Clinical features and pathological joint changes in dogs with erosive immune-mediated polyarthritis: 13 cases (2004-2012). Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 249(10):1156-1164. doi: 10.2460/javma.249.10.1156

Specht, A., & Guarino, A. (2019). Canine immune-mediated polyarthritis: Meeting the diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. Today’s Veterinary Practice, 9(5).

Retrieved from: https://todaysveterinarypractice.com/internal-medicine/canine-immune-mediated-polyarthritis-meeting-the-diagnostic-and-therapeutic-challenges/

Stull, J. W., et alia. (2008). Canine immune-mediated polyarthritis: Clinical and laboratory findings in 83 cases in western Canada (1991–2001). Canadian Veterinary Journal, 49(12), 1195–1203. doi: PMC2583415

Wilson-Wamboldt, J. (2011). Type I idiopathic non-erosive immune-mediated polyarthritis in a mixed-breed dog. Canadian Veterinary Journal, 52(2), 192-6. doi: PMC3022464

Figure One. Classification of canine polyarthritis or polyarthropathy

Max: A rescue success

Max (pseudonym) is a male flat coated retriever aged five years who has gained confidence exponentially since he was rescued in 2021. Recently, on a very pleasant autumnal day Max went out in the freshly cleaned car with his two guardians to a brook where he likes to paddle. A good time was had with the paddling. Going back to the car, the gate to an enclosed area was open – the gate that leads to the place where cow waste and other detritus are heaped. Alas Max found a nice, deep slurry pool to roll in – until he was dripping! The car door had been opened for him, and before the guardians could react, he jumped in…and shook. Oh….my! There were pools of wet slurry on the protection cover on the back seat, all the exposed seats in range were covered, all the doors and the inside car roof too! It even extended to the dashboard and windscreen.

The 10 minute drive home was not much fun…

The guardians spent the next hour plus, washing Max, washing the protection cover and their clothes, and starting to clean the car – in part. It needed several “cleans;” how quickly things can change, in this case, from sparklingly clean to anything but!

Conclusion

As the year draws towards its end it seems there are many people who would like to adopt a flat coated retriever to judge from the inquiries the FCRRN have received and our waiting list. Also it seems that there are more behavioural problems appearing in flat coated retrievers who have spent a substantial proportion of their lives in COVID-19 lockdowns(3) which is a situation of concern. Furthermore there is an increasing trend for surrendering guardians to use the Internet and other personal routes for a rehoming.

There is clearly a need for the FCRRN as evidenced by the number and range of contacts to us(2,3,4). We hope these contacts are a reflection of our commitment to improve the quality of life of a flat coated retriever in need and to build trust with the surrendering guardian, potential adopters, and the actual adopting guardian(1).

Finally, please could you remember the FCRRN if, via any route, you learn that a surrender or adoption is being considered.

Dr Iain J Robbé

On behalf of the Flat Coated Retriever Rescue Network (FCRRN)

Email: walesandwm@gmail.com

“Rescues R Us”

Experts: none of the FCRRN is acting in the capacity of an expert; each contributor is offering their advice based on accessible evidence. If you are concerned about any subject in the newsletters then you should consult a veterinary professional, legal professional or other professional.

© 2022 Flat Coated Retriever Rescue Network

(1) http://www.iainrobbe.com/fcrrn_01/

(2) http://www.iainrobbe.com/fcrrn_02/

(3) http://www.iainrobbe.com/fcrrn_03/

(4) http://www.iainrobbe.com/fcrrn_04/